“It must be asked here: why does the patient go on being worried by this that belongs to the past? The answer must be that the original experience of primitive agony cannot get into the past tense unless the ego can first gather it into its own present time experience…In other words, the patient must go on looking for the past detail which is not yet experienced. This search takes the form of a looking for this detail in the future.”

“It must be asked here: why does the patient go on being worried by this that belongs to the past? The answer must be that the original experience of primitive agony cannot get into the past tense unless the ego can first gather it into its own present time experience…In other words, the patient must go on looking for the past detail which is not yet experienced. This search takes the form of a looking for this detail in the future.”

D.W. Winnicott named the gesture of looking for the missing detail that explains the bad feeling, the missing experience, the longing for what had never been. The unnamed hurt seeks to know itself in the present. This is called enactment. I watch myself enact my own search for the detail that explains as I lay out my selfies for an art class. I want to know why I feel unlovable, despite all the joy I am lucky to have.

Selfies– I don’t look at my face to see how I look: I look at my own face to understand how it happened. I search my face for the reason, for a mark that designates my low status, something that justifies my silence. But all I see is a face that exists for others, a lined face, eyes wide with why.

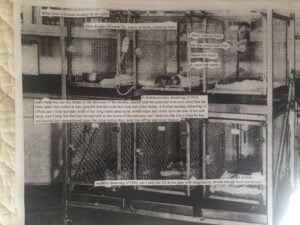

To follow Winnicott’s account, broken bonds that happen before language and the self are formed cause pain that cannot be fully experienced by the baby. Lack and absence are compounded twice—first as pain in the body and second as relational pain caused by the missing attunement the infant requires to hold/experience the feelings. It ends up that absence needs presence to be processed. Without being processed, the pain becomes an injury. It stays hidden, memorialized by rigid self-protective infrastructures, there everyday yet somehow unnamed, existing and not existing in that way psychological experience does. The injury, now encased, defies time. It collapses the present into the past unexpectedly. I became obsessed with these themes in my novel, The Monkey King. These monkey images– one of monkeys in a lab allowed companionship, and another, a collage I made using images from Harry Harlow’s lab in the 1960s with my attachment poetry glued on top–capture something so essential. When injured, healing is a kind of recovery. We don’t reclaim what was lost. We look for it in the present, in the future, as Winnicott explains.

I look in the mirror, I time travel backward and forward, the line of “me” strung between now and then. I search my face. The gap widens. I cannot see my face until I find that ancient injury, encased in a feeling, and give it what it needs—warm eyes, velvet soft sounds of interest, attunement in a nervous system fully formed.

I look in the mirror, I time travel backward and forward, the line of “me” strung between now and then. I search my face. The gap widens. I cannot see my face until I find that ancient injury, encased in a feeling, and give it what it needs—warm eyes, velvet soft sounds of interest, attunement in a nervous system fully formed.