The first public viewing of The Dinner Party (TDP), scheduled for March 14, 1979, represented the finish line for Judy Chicago and the project’s staff and volunteers. No one had yet seen it assembled in its monumental totality. Installing TDP took two weeks. The studio crew put up the special lighting to illuminate the Heritage Floor, assembled the floor’s 2,400 glossy porcelain triangles, tested and retested the tables to ensure they could bear the weight of the carved plates, and hung the six colorful opening banners, the eight Heritage Panels, and the photo documentation of the studio workers, the Acknowledgement Panels. The linen cloth that covered the tables took hours to iron before the runners could be laid on top and the chalice and flatware secured. Susan Hill tried to warn the museum electrician that running six irons at once might blow the circuits but was brushed off with a “don’t be silly.” As they got started, the entire floor went dark. On and off during the installation, Hill’s anxiety got the best of her and she would run to the nearest bathroom to throw up. Hill recalled that the runners and the lace millennium triangles that covered the table’s three corners were “finished at 10pm exactly, on Saturday March 10, as the security guards (hired to stay late with us) were closing up the museum. It was four days before opening, and the needlework was finally finished. We went out dancing.” Seeing it for the first time proved to be an emotional experience for Chicago and the other workers. Hill experienced it “like a blow to the gut.” She and ceramicist Judye Keys “were stunned… I was terrified and overwhelmed and had to stretch to accept it, literally learn to internalize it all.”

The first public viewing of The Dinner Party (TDP), scheduled for March 14, 1979, represented the finish line for Judy Chicago and the project’s staff and volunteers. No one had yet seen it assembled in its monumental totality. Installing TDP took two weeks. The studio crew put up the special lighting to illuminate the Heritage Floor, assembled the floor’s 2,400 glossy porcelain triangles, tested and retested the tables to ensure they could bear the weight of the carved plates, and hung the six colorful opening banners, the eight Heritage Panels, and the photo documentation of the studio workers, the Acknowledgement Panels. The linen cloth that covered the tables took hours to iron before the runners could be laid on top and the chalice and flatware secured. Susan Hill tried to warn the museum electrician that running six irons at once might blow the circuits but was brushed off with a “don’t be silly.” As they got started, the entire floor went dark. On and off during the installation, Hill’s anxiety got the best of her and she would run to the nearest bathroom to throw up. Hill recalled that the runners and the lace millennium triangles that covered the table’s three corners were “finished at 10pm exactly, on Saturday March 10, as the security guards (hired to stay late with us) were closing up the museum. It was four days before opening, and the needlework was finally finished. We went out dancing.” Seeing it for the first time proved to be an emotional experience for Chicago and the other workers. Hill experienced it “like a blow to the gut.” She and ceramicist Judye Keys “were stunned… I was terrified and overwhelmed and had to stretch to accept it, literally learn to internalize it all.”

Supporters, fans, and friends of the artists and workers crowed the March 14 opening night. Former Chicago student Suzanne Lacy and DP studio member Linda Preuss invited women around the world to hold dinner parties in honor of TDP and to honor historical women in their local communities. This International Dinner Party, the two artists explained, would be “a living art work … if each of our dinner parties occurs on the evening of March 14, we will form a continuous 24-hour celebration around the world.” Lacy sent out 1,200 announcements. Telegrams poured in during the opening, and the artists pinned small red triangles on a map of the world where dinner parties were held. Women in two hundred cities participated.

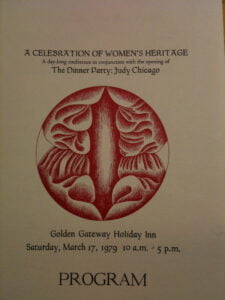

Poetry readings, panels, and workshops ran throughout the weekend. Chicago lectured to a sold-out crowd on Friday. On Saturday, an all-day conference titled “A Celebration of Women’s Heritage” took place at a nearby Holiday Inn. Art critics Lucy Lippard and Jan Butterfield, art historian Ruth Iskin, Lacy and Diane Gelon lead a panel discussion in the morning on the subject of “women’s art as a vehicle for social change.” Afternoon talks included those by Susan Rennie on witches and Amazons, Valerie Mathes on American Indian women, Raye Richardson on Sojourner Truth, and Arlene Raven on Natalie Barney and the “feminist lesbian tradition.” Three scholars from Stanford—Harrianne Mills, Marilyn Skinner, and Bella Zweigh—discussed women in the ancient world and M. J. Hamilton from Cal State University presented on the “alternate lifestyles” of medieval nuns. A workshop ran for children on the art of TDP.

Poetry readings, panels, and workshops ran throughout the weekend. Chicago lectured to a sold-out crowd on Friday. On Saturday, an all-day conference titled “A Celebration of Women’s Heritage” took place at a nearby Holiday Inn. Art critics Lucy Lippard and Jan Butterfield, art historian Ruth Iskin, Lacy and Diane Gelon lead a panel discussion in the morning on the subject of “women’s art as a vehicle for social change.” Afternoon talks included those by Susan Rennie on witches and Amazons, Valerie Mathes on American Indian women, Raye Richardson on Sojourner Truth, and Arlene Raven on Natalie Barney and the “feminist lesbian tradition.” Three scholars from Stanford—Harrianne Mills, Marilyn Skinner, and Bella Zweigh—discussed women in the ancient world and M. J. Hamilton from Cal State University presented on the “alternate lifestyles” of medieval nuns. A workshop ran for children on the art of TDP.

Most impressive, by any measure, were the crowds who lined up to see the exhibit. For much of its run in San Francisco, people waited for three, four, or five hours. Audience anticipation, particularly in California, had been building for months as a direct result of Gelon’s publicity and fund-raising efforts. That, coupled with steady regional press coverage, set the conditions for what became a major event. SFMOMA director Henry Hopkins recalled in a 2007 interview that the show saved the budget that year. “Lines of people coming in every day. People very deeply involved in the arts, people involved in ceramics, people involved in fabric work and things, with the runners on the table, feminists. But there was a big male audience, as well. Events outside the museum of people protesting, giving support, and it went on and on.” All told TDP broke the museum’s previous attendance records. Over 90,000 people came during the twelve-week exhibit.

During the long wait times, the lines sometimes erupted into spontaneous, temporary feminist communities. Jean A. Rosenfeld, from Carmichael, California, described her experience of being in line for three hours: “I began chatting with the woman behind me—and the chatting became sharing—personal and political and useful talk. And then as we rounded the corner to the final waiting hall, a small group of people began to sing. They sang quietly and beautifully and were surprised by the applause. Then the singing spread to the people around them—and then everyone was singing. All the people waiting, gathered into the final hallway, sang. Several hundred people sang in harmony—church songs, Hebrew songs, children’s rounds, sixties songs, spirituals. It was glorious.”

The anticipation of seeing the piece contributed to the excitement for those who waited in line. But many who had only moment before pressed eagerly forward, slowed to a crawl as they stepped into the dim gallery, creating long lines and long waits. People positioned themselves on the viewing side of the guardrail and started forward in the snaking line to see the first wing of goddesses and the shimmering floor and golden stream of names. TDP catalogue, purchased for less than a dollar, gave more details about what they were seeing, connecting the names on the floor to the seated guests. Heads bent as viewers moved closer to take in a detail, paused to look across the Heritage Floor, gazed at the back of a runner, or lingered over a particularly vivid plate. Some took advantage of the guardrail to kneel and study the embroidery of a runner. One visitor explained the impact of the staging and why it made her cry. “I entered TDP and saw the names all there together in one place for the first time in my life and I wept with joy…Why did it take so long? Why did we have to unearth these women buried and obliterated? Why do the power-holders even now try to keep such beauty and such strength and such worth invisible? Denied?”

The anticipation of seeing the piece contributed to the excitement for those who waited in line. But many who had only moment before pressed eagerly forward, slowed to a crawl as they stepped into the dim gallery, creating long lines and long waits. People positioned themselves on the viewing side of the guardrail and started forward in the snaking line to see the first wing of goddesses and the shimmering floor and golden stream of names. TDP catalogue, purchased for less than a dollar, gave more details about what they were seeing, connecting the names on the floor to the seated guests. Heads bent as viewers moved closer to take in a detail, paused to look across the Heritage Floor, gazed at the back of a runner, or lingered over a particularly vivid plate. Some took advantage of the guardrail to kneel and study the embroidery of a runner. One visitor explained the impact of the staging and why it made her cry. “I entered TDP and saw the names all there together in one place for the first time in my life and I wept with joy…Why did it take so long? Why did we have to unearth these women buried and obliterated? Why do the power-holders even now try to keep such beauty and such strength and such worth invisible? Denied?”

A journalist from Newsweek reported that women comprised 75% of the visitors to the San Francisco exhibit, noting with an air of surprise that “they seem to take palpable pride in the work. They joke a little about the vaginal imagery and admire the art. They seem to fill in the place settings, making the table their own. Many, when the recognize Chicago, go up to her and say, “Thank you. Thanks very much.” The imaginative act of “filling in” the place settings with themselves captured the sense of engagement many viewers had with TDP. Witnessing the current between the audience and the art, SFMOMA director Hopkins took heart from it. He told the San Francisco Examiner that, “TDP’s appeal to me became even stronger as I watched during the twelve weeks the power it held. It remained in pristine condition; no one tried to touch it. The audience found it a real experience. That’s art.”

Jane Gerhard, The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007