I recently had the pleasure of being interviewed for a writing class called Pencil to Paper, hosted by Krista Rolfzen Soukup at Blue Cottage Agency The teacher, award winning author Candace Simar, sent me some excellent prompts, one of them being about setting and its place in my work. So far, my published work is non-fictional and my unpublished work is fictional. I have two novels (and one memoir). One may imagine that setting plays a different role in a historical account than it might in a fictional one.

Or does it?

In my experience, it doesn’t.

In both kinds of writing, setting is most effective when it is rendered dynamically. In other words, it shouldn’t operate as a mere backdrop to plot; it should be involved in the grand effort or mechanics of telling a compelling story, be that story classified as history or fiction. In many ways (and this certainly isn’t an original idea), setting is best handled as you might a character—alive, changing force, contributing to the plot, the action and ultimately, the meaning you hope your reader to make from your words.

Two examples from my work jump to mind as rich instances from which to teasing out the valuable role setting can play. The first comes from my history of the feminist artist, Judy Chicago. First the backstory: in 1977, Judy Chicago set off to build a monument to women’s history, which she called The Dinner Party. There, 33 great women of history would take their seats at a triangular table where place settings commemorating the woman’s life and contributions were royally laid out. Goddesses sat along one wing of the table, visionaries, musicians, religious leaders, and queens along the second, and political activists, artists, doctors and other groundbreaking rebels the third. Each woman had an elaborately embroidered tablecloth, a carved porcelain butterfly-vulva plate representing various stages of liberation, and cutlery. The table rested on a triangular floor where the names of 999 other women flowed in streams (networks really) of female achievement, visually representing the truth that no one accomplishes great things alone.

Back to setting. Chicago had undertaken a massive project and came to see that she needed help to complete it. In the summer of 1977, she opened her studio to volunteers, a violation of the 20th century definition of the solo (white male) artist as genius that was (and is) currently in vogue. Over the next two years, hundreds of women devoted one, two, five days a week for two years to complete Chicago’s ambitious work. My history of The Dinner Party left the art evaluation to the experts and instead focused on the incredible (feminist) reality taking place within that studio in this short span of time. Women came to the studio to help the artist but they also came to contribute to the great work, writ large, of women’s history. They wanted the world to learn what they came to know in the studio, that a tradition of women’s contributions in the past had been systematically forgotten. This invisible history of women’s cultural, spiritual and political leadership had been written out of history. The Dinner Party would right that wrong.

The setting of the studio thus became a living space where the values and ideas of the feminist movement played out. Volunteers read feminist writers, they held consciousness raising groups, they learned women’s history, they reimagined their own lives. The setting of the studio literally embodied the values of 70s feminism, as represented by Judy Chicago. I spent a year reading Chicago’s archives at the Schlesinger Library where I found hundreds of small stories of women’s experiences working there. You can read more about it in my book, The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism.

The takeaway here is that setting became a way for me to develop plot and character. The studio setting offered me a set of plot points: when did Chicago open the studio to volunteers and when did she close it? How long was a volunteer shift? How was the studio laid out? Who made the rules and who enforced them? What activities were mandatory and why? The setting offered me another location to understand the meta values of women’s liberation that bore down on the physical space in that moment in time. It literally embodied the character of American feminism, warts and all. Plus, so much drama happened within those four walls! The ups, the downs, the fights, the reconciliations, the loves, the break ups, the miscarriages, the choice to end a pregnancy, sexual violence, coming out–you name it, it happened to the women at the studio. And because of that studio, such ordinary (and extraordinary) details ended up in a fancy archive at Harvard.

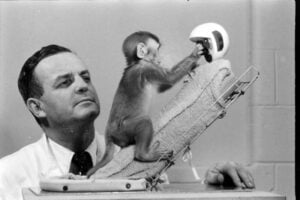

The second example of setting I wanted to point out comes from a novel I wrote about the infamous researcher who used baby monkeys to prove that love mattered more than food, the psychologist Harry Harlow. In The Monkey King of Madison, I recreate the insides of a primate lab in the years between 1930 and 1970, the years when primate research became the cutting edge of biological and psychological research (and received federal funding, thanks in part to Harlow). Now, you may know this already but primate labs are not easy places to get to know. Thanks in no small part to PETA activists, these spaces are embattled and guarded from anyone except the researchers and staff. This meant that I had to “look around the corners” of published articles for the stray detail, the accidental glimpse at what a primate lab looked like, sounded like, smelt like and how it was laid out architecturally. I did visit the Harlow lab at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and sat in the conference room where Harlow met with his students and staff. There was even one of his famous surrogate mothers, cloth covered and zombie-like as ever. I absorbed details from sitting in that setting. Do so help me reproduce it on the page as a character.

Establishing the lab as a dynamic setting for the novel took the most time and effort on my part. I read everything I could find, including memoirs, histories, PETA accounts, and all of Harlow’s 100 plus published articles. My challenge was to represent the lab as both a place of cruel indifference and a workplace where nice midwestern men and women worked 9-5, five days a week for years. It had to be honest. The lab was a place where a gregarious, creative, brilliant researcher charmed his students, staff and co-workers, as well as a place where nice men and women routinely took baby monkeys from their mothers five hours after birth, a place where monkey mothers cried, where baby monkeys cried, and where no human seemed to care about their pain. It had to be a character as complex as Harry Harlow himself.

I am happy to report that the hard feelings which came up for me (and for any reader with compassion) when contemplating a primate lab have been transformed in my novel by all the tools of a novelist—dream states as vivid as Alice in Wonderland and The Christmas Carol. I couldn’t leave those monkeys in that place! No way! Thank goodness for fiction! Sometimes history is just too damn hard.

These examples of setting, both of which use historical research to establish their realities, became the opposite of static buildings where action took place. They became the embodiment of action, saturated with character and complexity, all in the service of telling an effective story. In this way, fiction and nonfiction are not so different after all.